Kevin Sweeney

Interview featuring Kevin Sweeney’s series The Central Valley

AB: Based on the research you did prior and believing that Central Valley was an “otherworldly landscape full of extremes,” how did exploring the Central Valley for yourself change your perception? How did the conversations you had shift your perspective?

KS: Most people’s only experience with the Central Valley of California is taking the I-5 highway from L.A. to San Francisco. The endless mirage of farmland is staggering, and depending on the time of year, sweltering heat or dangerous “Tule fog” blankets the region.

The Valley immediately intrigued me when I moved to California, and at some point, I knew I would do a photo project about it. While researching, I discovered that an amateur historian named Frank Latta had made a riverboat trip in 1938 from Bakersfield at the southern tip of the Valley to San Francisco. It doesn’t take much knowledge of California’s current water crisis to wonder just how that could have been possible. With that trip in mind, I used the dried-up riverbeds as a route through the Valley.

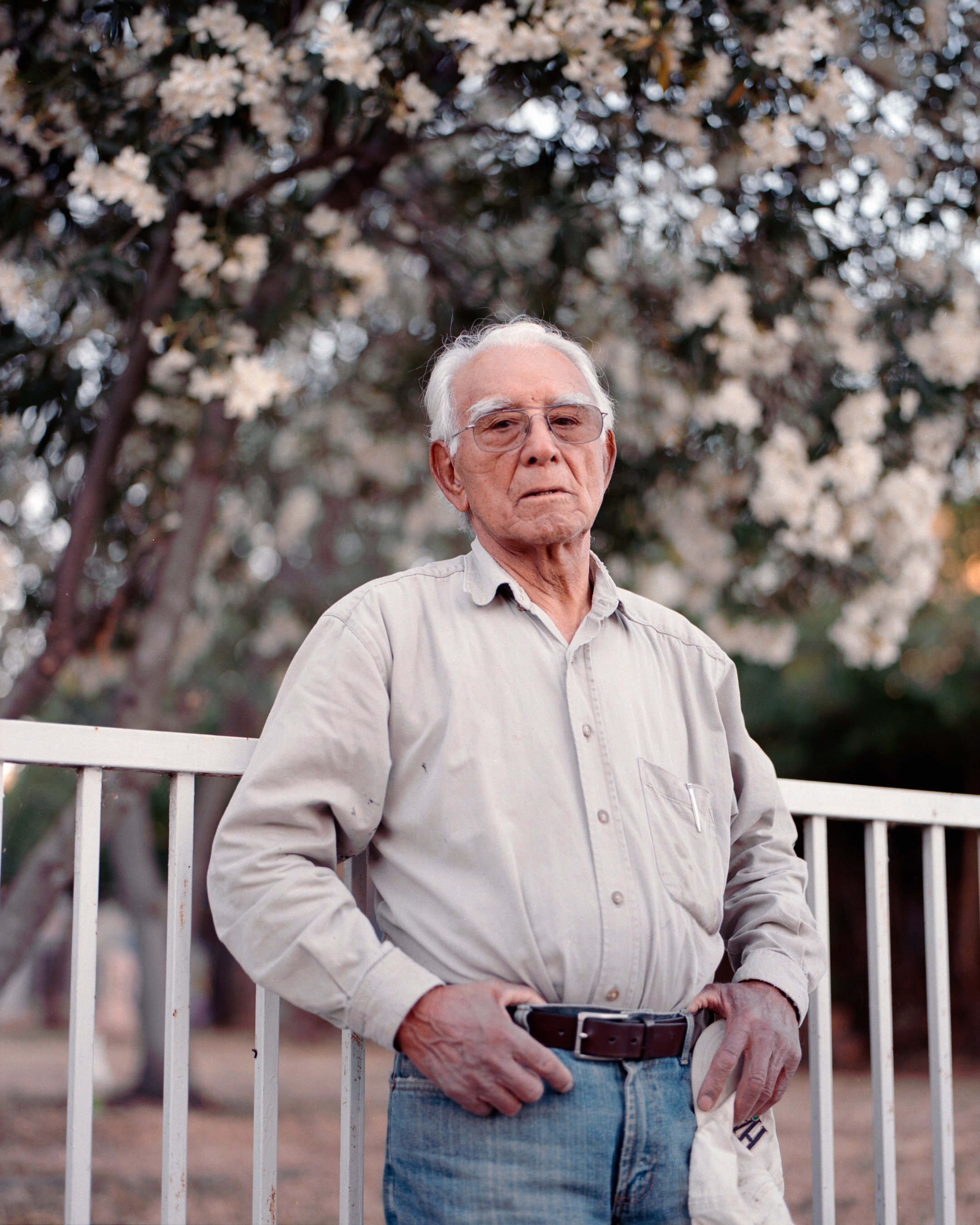

I initially planned to photograph agricultural topography, but this quickly changed as I spent most of my time on the streets of small cities and towns like Bakersfield or Tranquility. I learned that the people and landscape of the Valley shared more qualities than I could have imagined. Both had been disregarded, overworked, and controlled by the big agriculture companies that dominated the region. This “other” California is responsible for a large portion of America’s fresh produce, but we hardly ever hear about those communities that make it possible. This realization was the catalyst I needed to make the project more about the people rather than the landscape itself.

AB: How did you go about approaching people? How does each person help tell the story of the Central Valley?

KS: Full disclosure, I’m an introvert. Spending the day approaching strangers and initiating the awkward dance of asking for a portrait is exhausting. However, I always gravitate toward portraiture because of how rewarding those exchanges can be.

Photographing the Valley started as a way to force me back into the world after a year of the pandemic. Approaching subjects on the road was more straightforward because of the heightened sense of urgency. Some days would begin with rejections, but the repetition and rush from making pictures would melt away any apprehension I had. I was then free to approach anyone or go anywhere.

I’m more interested in photography’s power to suggest a sense of place, so I think that viewing the portraits as a set is far more meaningful than trying to tell any individual stories. Frank Latta interviewed thousands of Central Valley characters. Although I could never really get at the heart of the Valley as he did, I tried to embody the spirit of his work by reminding myself that we are in contact with remarkable people daily and often fail to recognize that fact.

AB: How do the photographs you currently have for this series start to create a portrait of place? Have your conversations with locals helped guide what you feel is missing or needs to be included?

KS: Creating a portrait of place was something I was cognizant of from the get-go. The Central Valley sun is oppressive. Sacramento Native Joan Didion described the Valley as "so hot that the air shimmers and the grass bleaches white, and the blinds stay drawn all day, so hot that August comes on not like a month but like an affliction." I tried to approach the sun with that quote in mind and went against my instincts as a photographer. I purposely shot in the mid-day sun to capture that bleached white look. It was also a pragmatic decision to allow me more time to work on the limited road trips I was doing.

Although I focused primarily on portraiture, I did plenty of landscape work that I think does a better job of tying up these portraits to a sense of place. Having those images included creates breathing room between each picture. I once heard the photographer Gregory Halpern describe landscapes as a form of portraiture and how a house can look like a face. I try not to see the difference between landscape and portraits but rather how they complement each other.

Regarding the conversation with locals, I think it just goes back to the limitations of photography. Your experience with people can't really ever be expressed through the medium. I try to separate the two to avoid disappointment once I finally see the negatives.

AB: We have gone back and forth about when to feature this series for an interview, you mentioned that it isn't complete yet but you are willing to share it in its current state. Why was it important to you to put the project on hold? How has the distance from it helped you better understand the project?

KS: The decision to put this project on hold was more practical than anything else. I moved away from California, so I won't be able to travel back to the Central Valley as much. I'm closer to where I grew up in New England, and my work has shifted to a new project focusing on that region. Like I said earlier, my road trips through the Central Valley started as an exercise in getting back out in the world to approach strangers. So just for that, I'm happy to share it even though it didn't come out as planned. When I moved, I considered this work a failure, but time has helped to change my perspective. I see it more as a rebound project from the pandemic, and now I've been able to shoot more freely because of it. I'll travel back at some point to continue it, but I think the work will look much different. My tastes and the equipment I'm using have already started to evolve.

Keep up to date on Kevin’s latest work by following along here:

Website

Instagram